Recently,

a study appeared in the journal Nature proposing a previously unsuggested start date for the Anthropocene: 1610 CE. It may seem, at first, a strange year to choose. It doesn’t have any obvious connection to the events we usually think of as tied to climate change, nor to the “great acceleration” that began in the mid-20th century. Still, 1610 has a lot to recommend it. As Simon L. Lewis and Mark A Maslin, the climate scientists who authored the proposal, comprehend it, it holds the potential to reorient the way we think about the Anthropocene, to help reconcile the quest for dramatic change in environmental policy with ongoing movements for social justice.

Most people reading this will, I think, have heard of the Anthropocene by now; indeed, given the extensive reporting on the concept, the Anthropocene may have greater name recognition than the Holocene, the geological epoch in which we officially still live. But in case you’ve missed it, “Anthropocene” is the proposed stratigraphic name for a new slice of geological time, an epoch made distinct by significant, measurable human impact on the earth and its climate.

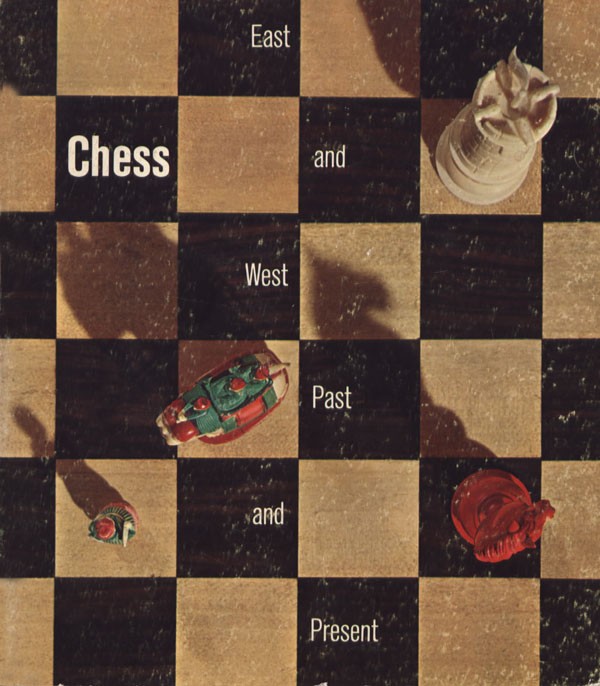

2012 Chronostratigraphic Chart

Stratigraphy organizes the vast geological timescale according to significant and demonstrable changes to the planetary system, so the Anthropocene proposal—formally tendered in 2008—is no casual matter: if it happens, it will be a new recognition that humans have changed not only the earth’s climate, but the earth itself. The International Committee on Stratigraphy, the group that oversees the divisions recognized in the International Geologic Time Scale, has

formed a committee to consider the question, and hopes to decide the issue by next year.

“Holocene,” the name for the epoch in which we officially still live, was adopted in 1885, a half-century after Charles Lyell’s demarcation of the “Recent” epoch by the end of the last Ice Age, some 11,500 years ago. Holocene means “wholly recent,” so the decision to bring this epoch to an end would mark the present as a peculiar time, after the recent, a time out of time in more than one sense. The move to recognize the Anthropocene is, in effect, a move to double the present, to see it from the perspective of another moment as well as our own. But what we can see from that doubled place depends on where we locate that other moment.

There are numerous contestants for the Anthropocene’s “Golden Spike,” or Global Boundary Stratosphere Section and Point (GSSP), the site that marks a recognized division in the geological timescale by pinpointing the planetary material that justifies the divide. The earliest would place the start date between six and eleven thousand years ago, based on the adoption and spread of agriculture, since the land-clearing it required necessarily altered the earth’s atmosphere.

But this would be tantamount to saying that the Anthropocene is equivalent to human life as we know it; by linking climate change to something we cannot imagine undoing—very few people are advocating a return to hunter-gatherer status—it would effectively remove any political energy the term might have. And the Anthropocene is, at base, a political strategy, notwithstanding its scientific verifiability; its intent is not simply to carve humanity’s name upon the stratigraphic map (humans, after all, invented the map in the first place), but to raise awareness of the negative planetary impact of certain human activities, with the intent of altering or mitigating them.

Plastic Rocks

Other proposed GSSP sites include Holocene ice cores that reveal rises in methane and carbon dioxide around the late eighteenth century, the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, when fossil fuels began to be widely used, with increasingly devastating effects on atmospheric carbon; highly-leaded soils affected by mining and the use of leaded gasoline; the apparent

creation of a new form of rock out of plastic, which marks the mid-to-late 20th century as a moment when human garbage took on a geological life of its own; and radio-isotopes detectable in the planetary rock record which record the detonation of nuclear bombs.

1610, the date proposed by Lewis and Maslin, who hold positions in Climatology and Global Change Science in the Geography Department at University College of London, works a little differently. It was chosen because it was the lowest point in a decades-long decrease in atmospheric carbon dioxide, measurable by traces found in Artic ice cores. The change in the atmosphere, Lewis and Maslin deduced, was caused by the death of over 50 million indigenous residents of the Americas in the first century after European contact, the result of “exposure to diseases carried by Europeans, plus war, enslavement and famine” (Nature175).

The destruction of the indigenous population (leaving only an estimated 6 million survivors on both northern and southern American continents by the mid-17th century) meant a significant decline in farming, fire-burning and other human activities affecting atmospheric carbon levels. Lewis and Maslin point to other geologically significant aspects of Euro-American contact as well, including the transfer of plant and animal species between Europe and the Americas, leading to a significant loss of biodiversity and acceleration of species extinction rates. From this view, the Anthropocene develops alongside the global pathways of modernity. Lewis and Maslin term this proposal the “Orbis hypothesis,” from the Latin for “globe.”

Lewis and Maslin’s proposal is compelling because it is, as far as I know, the first proposal for an Anthropocene “golden spike” to recognize genocide as part of the cause of epochal division. Geologists have long known that European settlement was accompanied by a dramatic upsurge in extinction rates. Charles Lyell, in the second volume of his foundationalPrinciples of Geology (1832), justified this as simply in the natural order of things:

“[T]he annihilation of a multitude of species has already been effected, and will continue to go on hereafter….as the colonies of highly-civilized nations spread themselves over unoccupied [] lands…Yet, if we wield the sword of extermination as we advance, we have no reason to repine at the havoc committed, nor to fancy with the Scotch poet that we ‘violate the social union of nature’….We have only to reflect, that in thus obtaining possession of the earth by conquest, and defending our acquisitions by force, we exercise no exclusive prerogative. Every species which has spread itself from a small point over a wide area must, in like manner, have marked its progress by the dimunition or the entire extirpation of some other…”

Lyell’s depiction of the devastating consequences of European conquest as just another natural cycle is belied by contemporary climate scientists’ recognition of its lasting effects as an ongoing unnatural disaster.

Lewis and Maslin identify the two factors most often cited in Anthropocene discussions—the anthropogenic change in atmospheric carbon levels and the homogenization of planetary biota—as an apres-coup to the event we know as “1492.” Numerous cosmologies hold that the Earth will remember acts of intra-human violence, that the planet itself will testify to the brutality humans have inflicted upon members of their own species. With the Orbis hypothesis, climate science may be counted among them.

For some, the Anthropocene debates seem irrelevant: does it matter where in the past geologists decide to place a golden spike, when such urgent questions remain about our future? But the liveliness of the discussion reflects the explanatory promise of the Anthropocene concept: it is a debate over what kind of story can and should be told about human impact on the planet. The claim is often made that climate change is simply too big to see—that it is what eco-critic Timothy Morton terms a hyperobject, something that cannot be realized in any specific instance. The Anthropocene offers climate change not just periodicity but narrativity. And like any well-told story, it relies upon conscious plotting and the manipulation of feeling.

Some insist that we are naming this story incorrectly—that “Anthropocene” obscures vital social and historical facts that must be addressed in any proposed solution. “Humans” as a whole are not responsible for causing the mess we are currently in, nor are they perpetuating it at equal rates. Naming the crisis after the species, they argue, hides the social, not geological, histories of exploitation (of humans and “nature” alike) at the root of the problem. It’s unlikely that we will find a single word that can accurately convey these histories (

Jason Moore’s “Capitalocene” falls short on aesthetic grounds, though

Jussi Parikka’s “Anthrobscene,” indexing the profound wastefulness of contemporary capitalism, may come closer.) Still, the Anthropocene story needs to find ways of communicating them, of refusing to generalize or naturalize the consequences of the past few centuries.

Photo Credit: Sea Change Radio

The Orbis hypothesis, in this respect, succeeds better than others, though it remains limited by standards of scientific verifiability. (What kind of geological trace, for instance, might inscribe the concurrent history of the Atlantic slave trade, also central to the dynamics and the devastation of “contact”?) And indeed, the desire to make the Anthropocene’s start date conform to established stratigraphic convention

seems to be pushing the ICS’s Anthropocene Working Group toward the mid-20th century, based on the dawn of the nuclear age, which, according to the group’s chair, Jan Zalasiewicz, left the first truly global and indelible marks in the planetary rock record. Lewis and Maslin’s report names the mid-20th century as a second option, though as they point out, the two origins have different implications: 1610 is broader, pointing to “colonialism, global trade and coal,” while the nuclear-age Anthropocene highlights an “elite-driven technological development” capable of laying waste to the planet almost instantaneously (

Nature 177).

In both cases, the Anthropocene story takes as its origin not simply human indifference to nature, but human disregard for other human lives. But the latter frame is too narrow, pointing toward abstractions like “elites” and “technology” instead of the histories of global striation that follow 1492. Sylvia Wynter,

in a brilliant account of the 1492 event, identifies it as the start date for a cognitive process that parallels, in some ways, the homogenizing effect on planetary life that Lewis and Maslin note. It is, she contends, the beginning of the global dissemination of a specifically Western idea of humanism that posits itself as universal but endlessly defers the truly universal distribution of the benefits it confers, one that legitimates and covers over the violence, racial, colonial and otherwise, done in its name.

The aftermath of 1492, Wynter shows, is the spread of a humanism that has failed much of humanity, a failure to which even the Artic ice cores can bear witness, and that in doing so has deeply damaged the planet as well: an inhuman humanism. The contradiction that some have seen in the name of the proposed epoch—that the “Anthropocene” was not brought about by all members of the species it names—is precisely the problem it is now up to us to solve.

Dana Luciano: Rocks and Ghosts